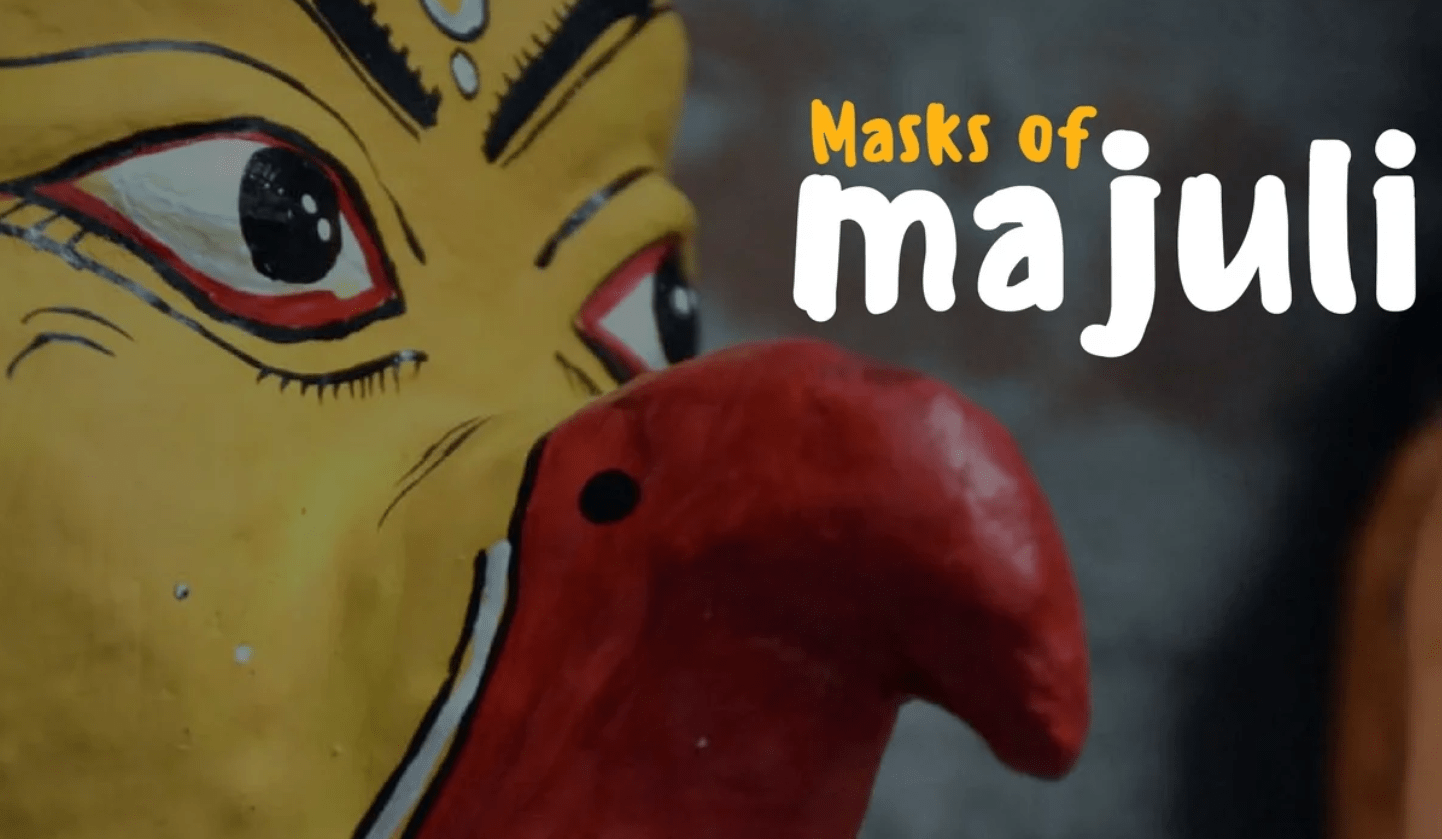

Masks of Majuli: In ancient times, the people of Majuli would hear a powerful voice emanating from the Brahmaputra River, repeatedly proclaiming, “Banhtote kathito, jopatote pachito,” which translates to “you will get a piece of split from a bamboo and a basket from a bamboo grove.” This mysterious voice encouraged them to master the art of mask making. Thus, the creation of masks became a vital cultural element in Majuli.

As we explored a room filled with detached heads, including the fearsome headless demon Kabandha, whose eyes and mouth are located on his stomach, we were captivated by the stories of Bhaonas, Satras, and the masks of Majuli.

Masks of Majuli, Assam

The Heritage of Majuli Masks

Majuli, renowned as the largest riverine island in India and possibly the world, is also a bastion of Neo-Vaishnavite tradition and culture. Although it is celebrated for its vastness, Majuli Masks is gradually disappearing.

Sri Shankaradeva’s visionary ideas transcended religious and cultural boundaries, blending devotion with art in a unique manner. The Satras (or Xatras) of Majuli, Vaishnavite ashrams that provide religious and cultural education, were influenced by his philosophies.

Sri Sankaradeva sought societal change rather than merely introducing a new religion. He used performing arts to convey his messages, composing plays about Lord Krishna and staging traditional performances known as Bhaona. Masks, initially made from various materials such as wood, clay, and earth, were later crafted from bamboo, making them lightweight and suitable for these performances.

The Present State of Majuli Masks

Today, not all Satras in Majuli continue the tradition of mask making. The craft is still preserved at Nutan Chamaguri Satra. During our visit, we entered a room brimming with masks—both large and small—depicting various mythological figures, reminiscent of the stories from Mahabharata and Ramayana.

The Satradhikari (Head of the Satra) Hem Chandra Goswami, a master craftsman and National award winner, has kept the art alive and thriving. Although we missed meeting him as he was in Delhi for a Republic Day Parade exhibition, Prasanna Goswami kindly shared his knowledge with us.

The Process of Mask Making

Mask making is a detailed process. It starts with creating a three-dimensional framework from local bamboo, woven into a hexagonal pattern. This framework is covered with cotton fabric dipped in a clay and cow dung paste, applied in layers. Facial features are then carved using specialized knives, and the masks are left to dry in the sun. Historically, natural colors were used, but now artificial colors are applied. Hair and mustaches are crafted from jute and water hyacinth. After these meticulous steps, the masks are ready for Bhaona performances.

Types of Masks

Masks are categorized into three types: Mukha (face masks only), Lotokai Mukha (masks with movable eyes and lips), and Bor Mukha (large masks covering almost the entire body). We observed masks of figures like Ram, Sita, Ravana, Narasimha, and the grotesque Kabandha. Today, smaller masks are also made for tourists as souvenirs, and some foreign visitors are even learning the art of mask making, reflecting how tourism is positively influencing the region.

Experiencing Bhaona

Having previously seen Gomira and Chhau performances, we were eager to experience a Bhaona. While the masks used in Gomira, Chhau, and Bhaona differ, and their dance styles vary, a common thread unites them: the dancers’ devotion and the theme of good triumphing over evil.